Archivists on the Issues is a forum for archivists to discuss the issues we are facing today. Today’s post comes from regular writer for I&A’s blog, Lindy Smith, Reference Archivist at Bowling Green State University’s Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives.

For my second in a series on Access and Accessibility in Archives, I will discuss physical access to collections and spaces. I did not want to cover physical accessibility since there was an SAA AMRT/RMRT Joint Working Group on Accessibility in Archives and Records Management that covered this in depth and has created excellent documentation for working with both patrons and professionals with disabilities.

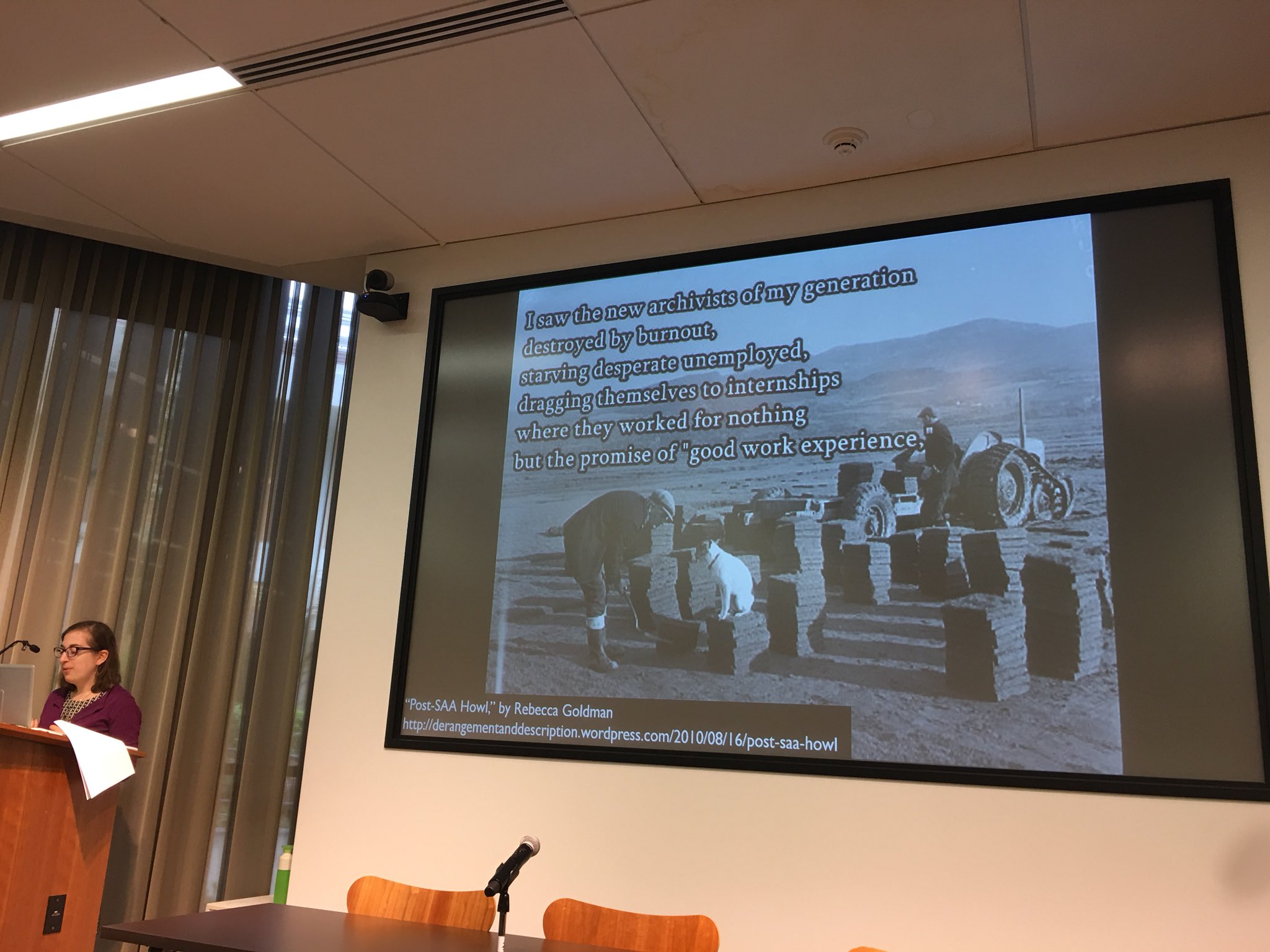

My initial thoughts were unfocused, though I knew I wanted to touch on this idea of who is, and more importantly, feels welcome in our spaces. I have been thinking about this since last spring, when I attended a presentation on art education and museum outreach, and last summer, when I read Cecilia Caballero’s blog post, “Mothering While Brown in White Spaces, Or, When I Took My Son to Octavia Butler’s Exhibit.” My thoughts congealed into a more digestible mass in my brain after I attended a fabulous session at the Midwest Archives Conference annual meeting titled “Beyond Description: Toward Critical Praxis in Public Services,” featuring Anna Trammell, Cinda Nofziger, and Rachael Dreyer as panelists.

These three occurrences gave me a lot to think about regarding the people in our reading rooms and what we can do to increase access and inclusion to a wider range of patrons. I hope we as a profession can come up with solutions to improve access to our physical spaces.

Director Dialogue: In Conversation with Brian Kennedy

Last March I attended a public discussion between three art museum directors about how they approach art education at their respective institutions: Brian Kennedy, director of my local art museum, the Toledo Museum of Art; Gretchen Dietrich from the Utah Museum of Fine Arts; and Lori Fogarty of the Oakland Museum of California. Though I went looking for outreach ideas, I came out with many questions, which I summarized on my own [sadly neglected] personal blog shortly after the event.

The directors discussed how they conduct outreach to make their museums into community spaces, better anticipate user needs, and invite more of the people from their respective neighborhoods into their buildings. Libraries, especially public libraries, have served the role of community centers for decades and museums are now getting on board, but where does this leave archives among our GLAM counterparts?

Archival public spaces tend to be limited to utilitarian reading rooms and maybe exhibit space. What would it look like if we tried to build new kinds of spaces where people could interact with our collections in different ways? What if we focused on more than research needs and looked at other information needs we could fill? What if we built spaces that are comfortable and appealing to spend time in? What if people didn’t have to sit at an uncomfortable table in a silent, surveilled room to get access to our collections? I am sure some of you reading this are thinking, “We’re doing something like this!” I want to hear about it! Do you have a good model others can follow? Shout it from the rooftops (or @librarypaste on Twitter)!

Beyond Description: Toward Critical Praxis in Public Services

During the MAC session, Trammel, Nofziger, and Dreyer began by presenting the idea of taking a critical look not only at our collections and our profession, but also the public services our staffs provide, using Michelle Caswell’s instant classic “Teaching to Dismantle White Supremacy” as a basis to examine the barriers that keep some users from accessing archives. Caswell’s article provides a useful diagram to provoke thinking about ways white supremacy shows up in our work; the area on Access/Use is particularly relevant to this discussion, but it only scratches the surface.

The second part of the MAC session was an interactive activity where the room broke into groups and filled out a rubric that had a much longer list of types of barriers along with space to include a description of specific barriers to help guide the group discussions. The categories listed were as follows:

- Technology (i.e. digital literacy)

- Physical (i.e. vision or mobility challenges presented by public spaces)

- Time (i.e. public hours, length of time required to conduct research, request and recall materials)

- Financial (i.e. costs involved with accessing archives)

- Documentation (i.e. registration requirements, identification required)

- Policy (i.e. restrictions)

- Identity (i.e. gender, sexuality, race)

- Institutional/Systemic (i.e. whose interests & history are represented by holdings?)

- Human Factor (i.e. customer service issues, approachability, etc.)

I found these categories to be excellent starting points to brainstorm. For the sake of (comparative) brevity, I will not go into all of them here, but I want to talk through a few to give examples of how to use them as inspiration for brainstorming. Full disclosure: some of these came up or were inspired by my group’s discussion and did not spring fully formed from my own brain.

First example: Cost is a huge barrier. Obvious costs include memberships to private libraries and historical societies, photocopying or other reproduction services, or private researcher time, but hidden costs like parking, transportation, childcare, time off work, food and accommodations if researchers are coming from out of town are also present. It is great to collect materials from underrepresented communities, but if members of those communities cannot afford to come see and use materials from their own lives and experiences, we are still only serving people with the means to visit. To mitigate this, archives could provide research grants to members of the communities targeted in collection development projects. Institutions could also take their work directly to those communities, rather than continuing on relying on patrons to do all the work of coming to them.

A second barrier: Time. Many repositories have limited hours, often because of limited staffing or other concerns that are seemingly insurmountable, but we should take a closer look at ways to make ourselves more available outside “normal working hours” (or 9-12 and 1-4, or afternoons two days a week, etc.). People who work have to take time from jobs to visit, and if they have limited or no paid time off, this is a costly proposition, especially if their research needs require multiple visits. Archives can at least test extended or flexible hours as their circumstances allow. What if a repository closed on Wednesday afternoons in order to open Saturday afternoons instead? What if academic archives used students to stay open on weekends? My repository is somewhat unusual in that we have a circulating collection in addition to our special collections; so we have longer hours than most special collections – when school is in session, we’re open until 10pm five days a week and Saturdays and Sundays). We only have four full-time and one part-time staff in our department, so our terrific student employees keep things running on evenings and weekends. Sometimes staff members take an evening shift, but we flex that time and take it off during the week.

“Mothering While Brown in White Spaces, Or, When I Took My Son to Octavia Butler’s Exhibit”

I stumbled across Cecilia Cabellero’s post via Twitter last fall and it hit me hard. It is worth a read, because we can see some of these issues in action in a real person’s real life. Rather than try to rephrase her words with my own [white] words, take a minute to read her post and reflect on the issues she raises.

Cabellero mentions a specific library, but let’s be honest: this could be many of our repositories. She identifies it as being in a white space, as many archives and special collections are. Started by a wealthy white man for the use of other wealthy white men. A place where researchers need to have advanced degrees or letters of reference to access collections. Who is served by these policies? What is protected? For those of us with less stringent admission guidelines, what groups are we still keeping out? Do you require photo identification? Do you charge membership or usage fees? Many of our policies have good reasoning behind them and we are not likely to update them anytime soon. Are there better ways to communicate that to our users?

Cabellero was visiting an exhibit about Octavia Butler, a woman of color who wrote science fiction at a time when neither women nor people of color were particularly welcome in that genre (I am sure many would argue they still are not, but things have improved). Regardless of the library’s intentions, they created an environment in which a female writer of color did not feel comfortable or welcome or allowed to visit an exhibit with personal resonance.

One of Cabellero’s main points, as evidenced by the title, is her experience parenting in our spaces. This deserves some examination for archivists. Do you allow children in the reading room? If not, do parents who want to use your collections have other options? Childcare is expensive and may not always be available at convenient times. This disproportionately affects mothers, who often take on more childcare labor, especially during weekdays when archives tend to be open.

How often do we exclude as Caballero was excluded, or on similar but smaller scales? How often do our minor interactions with patrons leave them feeling unwelcome? I am sure I have unintentionally done this in my work. What kind of image do we project and how does that keep people away? How do we make archival spaces that are really for everyone?

It Take a Long Pull to Get There

I do not have nearly as many answers as questions, but let us have these discussions and attempt solutions that better serve all potential users. It won’t be quick or easy, but it will be worthwhile.

I’ll leave you with one final illustration. I studied musicology in graduate school and I often think back to a point that one of my professors, Dr. Gayle Sherwood Magee, made about the importance of representation and access, as illustrated by the 1935 opera Porgy and Bess. A little background if you’re unfamiliar: it is very controversial because a group of privileged white men wrote about poor black characters so the script play into a lot of negative stereotypes: characters are beggars, drug dealers, abusive partners, etc. It gave African-American singers the opportunity to perform on Broadway, something that was still remarkable when Hamilton premiered with a diverse cast 80 years later, but none of the characters portrayed in the opera had access to be in the audience and watch their stories playing out on stage. Are we doing the same thing in archives by focusing our diversity efforts on our staffs and collections, and not the people coming into our reading rooms?

References

- Caballero, C. (2017 August 23). “Mother While Brown in White Spaces, Or, When I Took My Son to Octavia Butler’s Exhibit.” Retrieved from https://www.chicanamotherwork.com/single-post/2017/08/23/Mothering-While-Brown-in-White-Spaces-Or-When-I-Took-My-Son-to-Octavia-Butler%E2%80%99s-Exhibit

- Caswell, M. (2017). “Teaching to Dismantle White Supremacy in Archives.” The Library Quarterly, 87(3), 222-235. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/692299

- Trammell, A., Nofziger, C., & Dreyer, R. (2018 March). “Beyond Description: Toward Critical Praxis in Public Services.” Panel presented at the Midwest Archives Conference Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL.